Here’s a quartet of flickers playing down at the local Bijou, holdovers from a week or so back.

Top of the list is The World’s End, the third comedy from the team of writer-director Edgar Wright and writer-star Simon Pegg (we might as well add actor Nick Frost, since he’s prominently featured in all three himself). The team has come a long way since Shaun of the Dead (2004) and Hot Fuzz (2007), very funny movies, but which lack the technique and emotional vistas of this latest work.

Wright and Pegg have hit upon an approach that avoids formula as it allows for so many variations. Starting with a large cast of characters who are, each and every, victims of their own personalities, they bore in on the most socially marginal of the group. This hero – because that’s what he becomes – resents his marginalization to the point where he thinks he should be a model for, if not the whole of society, then for a very wide circle of his friends and acquaintances. He is not a reject, but a semi-voluntary non-conformist.

Wright and Pegg have hit upon an approach that avoids formula as it allows for so many variations. Starting with a large cast of characters who are, each and every, victims of their own personalities, they bore in on the most socially marginal of the group. This hero – because that’s what he becomes – resents his marginalization to the point where he thinks he should be a model for, if not the whole of society, then for a very wide circle of his friends and acquaintances. He is not a reject, but a semi-voluntary non-conformist.

Pegg, as always, plays the square peg (sorry) who can’t seem to find the right shaped hole. A now grown ne’er-do-well who lives by sponging off his more responsible, middle-class friends, he rounds four of them up to have a redo of a 12-bar pub crawl they weren’t able to complete the night of their secondary school graduation. So back to their quiet hometown they go and start all over again.

The sketches of the four friends is remarkably adept for a contemporary comedy (though it would have been considered par for the course in the 1940s). The pacing of the humor is sure and the big twist in the plot (analogous to those in the first two comedies) is unexpected and funny (at least if you haven’t seen the movie’s television commercials). In fact, the whole movie is funny, even when it slips in a soupcon or two of sentiment.

The sketches of the four friends is remarkably adept for a contemporary comedy (though it would have been considered par for the course in the 1940s). The pacing of the humor is sure and the big twist in the plot (analogous to those in the first two comedies) is unexpected and funny (at least if you haven’t seen the movie’s television commercials). In fact, the whole movie is funny, even when it slips in a soupcon or two of sentiment.

Lovelace is the second feature directed by the well-regarded documentary filmmakers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. As was the case with their first, 2010’s Howl, they are basing the movie on “real life,” in this case the story of Linda Lovelace, nee Boreman, the star of Deep Throat (1972), the porn film that made explicit sex on the screen not just acceptable but chic.

The two directors haven’t fallen into the trap of making a mere docudrama, but they have constructed a peculiarity that doesn’t offer much more. In essence, they use the first half of the movie to tell the old story of Lovelace and Throat, a popular yarn that emphasized sexual freedom, taboo-breaking, the thrill of celebrity, and oddball respectability. The second half, using Lovelace’s own 1980 autobiography, Ordeal as a resource, tells a much more harrowing and ugly tale of a woman brutally forced into a porn career by an abusive boyfriend.

The first story is told entirely objectively. Though Lovelace is the center of the camera’s attention, there’s no sense that we’re seeing the action from her or any other character’s viewpoint. That’s decidedly not the case with the second version of the tale, which begins with an older, wiser Lovelace beginning to write Ordeal and then proceeding to flashback.

The first story is told entirely objectively. Though Lovelace is the center of the camera’s attention, there’s no sense that we’re seeing the action from her or any other character’s viewpoint. That’s decidedly not the case with the second version of the tale, which begins with an older, wiser Lovelace beginning to write Ordeal and then proceeding to flashback.

The contrasting stories don’t seem to have much point. Anyone who saw Lovelace’s name during the 15 or 20 years she was in and out of the public eye knows what she wrote in 1980, even if they didn’t read it themselves. Is there anyone left out there who believes a career in porn is all party favors? Taken separately, the two halves of Lovelace are competent, if uninspired, pieces of filmmaking. Together, they are less than the sum of their parts.

The contrasting stories don’t seem to have much point. Anyone who saw Lovelace’s name during the 15 or 20 years she was in and out of the public eye knows what she wrote in 1980, even if they didn’t read it themselves. Is there anyone left out there who believes a career in porn is all party favors? Taken separately, the two halves of Lovelace are competent, if uninspired, pieces of filmmaking. Together, they are less than the sum of their parts.

Gosh, sex is dirty – but then, so is everything human, ain’t it? Welcome to Paul Schrader’s world where everything that isn’t tawdry is literally divine. A proponent of Calvinist views (that good works not only won’t get you into heaven, but aren’t even indications of worthiness) and, less so, Jansenism (the gift of grace can be less a blessing than a curse), Schrader is usually content to lay out these premises as finished statements which he then illustrates with pictures of varying solemnity.

The Canyons finds Schrader at his pedagogic worst; the movie, which is turgid in any case, can’t even rouse a spark of titillation from entwined limbs and bumping torsos – or the drug taking, the cruelty, the bitching and moaning and manipulating. It’s not even good soap opera, so Schrader has to force a potential for murder into the action in order to make it seem that something is at stake.

The Canyons finds Schrader at his pedagogic worst; the movie, which is turgid in any case, can’t even rouse a spark of titillation from entwined limbs and bumping torsos – or the drug taking, the cruelty, the bitching and moaning and manipulating. It’s not even good soap opera, so Schrader has to force a potential for murder into the action in order to make it seem that something is at stake.

The canyons of the title are those which surround and divide Los Angeles and which contain a large portion of the Hollywood “creative community” (as they like to be called). The little squared circle at the center of The Canyons involves a scuzzy producer, his girlfriend, an actor friend/former lover of hers, and a woman who just seems to be around for the sex.

The two guys struggle for the affections of, as opposed to mere access to, the girlfriend. At first, the producer is depicted as playing underhanded games, but, when it suits Schrader, it is revealed the actor is sort of a cheat himself. But that’s OK because… see above.

The two guys struggle for the affections of, as opposed to mere access to, the girlfriend. At first, the producer is depicted as playing underhanded games, but, when it suits Schrader, it is revealed the actor is sort of a cheat himself. But that’s OK because… see above.

Bret Easton Ellis wrote the screenplay, which guarantees the backdrop is in a legitimately unreal Elliswood. The Canyons also engages in stunt casting. Lindsay Lohan does on screen what the tabs say she does in her “private” life and an excruciatingly untalented porn actor plays the producer. Class all the way.

If Paul Schrader is deploying his old ideas – make that idea – Brian De Palma is recycling his fragmentary techniques in Passion, a thrill-free thriller. Everything you’d expect to see, you see. The plot features his standby doubling, with the tension between a businesswoman and her protégé mirrored by tension between the protégé and her protégé. His visual reflexes still spasm when hit with a hammer; for example, one character’s face is seen in a reflective surface so that we’ll know – as we know in nearly all De Palma’s thrillers – that she has a secret self.

If Paul Schrader is deploying his old ideas – make that idea – Brian De Palma is recycling his fragmentary techniques in Passion, a thrill-free thriller. Everything you’d expect to see, you see. The plot features his standby doubling, with the tension between a businesswoman and her protégé mirrored by tension between the protégé and her protégé. His visual reflexes still spasm when hit with a hammer; for example, one character’s face is seen in a reflective surface so that we’ll know – as we know in nearly all De Palma’s thrillers – that she has a secret self.

Based on Passion, it appears that De Palma has lost interest in everything aside from his own mechanical self. A movie isn’t a window to a world; it’s just a great big mirror filled with one tiny figure.

I don’t know about you, but I’d head for the pub crawl.

I don’t know about you, but I’d head for the pub crawl.

–Henry Sheehan

Europa Report, directed by Sebastian Cordero, is an intelligent addition to the list, particularly due to its additional dynamic, that of the group under psychological pressure, pressure that will force the group to cohere or disintegrate.

Europa Report, directed by Sebastian Cordero, is an intelligent addition to the list, particularly due to its additional dynamic, that of the group under psychological pressure, pressure that will force the group to cohere or disintegrate. Briefly, the plot, which is told retrospectively, is about a months-long expedition to one of Jupiter’s moon, Europa. Because of the possible presence of water, the moon is considered a likely home to cellular life and so a small crew of scientists and pilots have been sent out to take samples. This physically enclosed group have to endure the inevitable friction of cashing personalities, lethal accidents and, once they get to Europa, strange and deadly, if apparently primitive, life forms.

Briefly, the plot, which is told retrospectively, is about a months-long expedition to one of Jupiter’s moon, Europa. Because of the possible presence of water, the moon is considered a likely home to cellular life and so a small crew of scientists and pilots have been sent out to take samples. This physically enclosed group have to endure the inevitable friction of cashing personalities, lethal accidents and, once they get to Europa, strange and deadly, if apparently primitive, life forms.

Johnnie To is the best action director in the world and one of the greatest of all time. Full stop, period, the end. Many people would agree because of his movies’ most obvious virtue: Flabbergasting cutting that, once the bullets start flying (and boy, do they fly), is faster then, well, a speeding bullet.

Johnnie To is the best action director in the world and one of the greatest of all time. Full stop, period, the end. Many people would agree because of his movies’ most obvious virtue: Flabbergasting cutting that, once the bullets start flying (and boy, do they fly), is faster then, well, a speeding bullet. To’s brilliance, which can seem boundless, includes defining action as its absence. Typically during a To action film (he also makes comedies, romances and period films), there comes a moment when the characters come to a complete standstill, with even their faces frozen into emotionless masks. But there is a tension here – emotional torque – the signals an oncoming sequence of utter mayhem. I’m not sure there is anyone else in the world who can wring so much from a shot of someone just sitting there.

To’s brilliance, which can seem boundless, includes defining action as its absence. Typically during a To action film (he also makes comedies, romances and period films), there comes a moment when the characters come to a complete standstill, with even their faces frozen into emotionless masks. But there is a tension here – emotional torque – the signals an oncoming sequence of utter mayhem. I’m not sure there is anyone else in the world who can wring so much from a shot of someone just sitting there. Drug War is set in one of those vast, Chinese urban centers, full of industrial sites and cruddy-looking apartment buildings; it makes you wonder what people are ultimately waging war over. Although compared to the drug gangs the police don’t appear to be particularly brutal, they’re not above beating prisoners or like behaviors.

Drug War is set in one of those vast, Chinese urban centers, full of industrial sites and cruddy-looking apartment buildings; it makes you wonder what people are ultimately waging war over. Although compared to the drug gangs the police don’t appear to be particularly brutal, they’re not above beating prisoners or like behaviors. Maybe Chinese bureaucrats didn’t want to get in the way of a good movie. Because that’s what To has come up with. No, let’s allow the superlatives to flow, because Drug War has earned them. It’s exciting and mind-blowing – brilliant.

Maybe Chinese bureaucrats didn’t want to get in the way of a good movie. Because that’s what To has come up with. No, let’s allow the superlatives to flow, because Drug War has earned them. It’s exciting and mind-blowing – brilliant.

Reviews of animated features generally format themselves and Turbo, the latest from DreamWorks Animation, is susceptible to the same treatment. First comes a plot description (a garden snail with a need for speed finds himself suddenly capable of high velocity), an assessment of the animation in general (good) and of the character animation (fair to very good). Then a list of shortcomings (the set-up is overstated, the second half of the movie is yet another depiction of self-realization through contest).

Reviews of animated features generally format themselves and Turbo, the latest from DreamWorks Animation, is susceptible to the same treatment. First comes a plot description (a garden snail with a need for speed finds himself suddenly capable of high velocity), an assessment of the animation in general (good) and of the character animation (fair to very good). Then a list of shortcomings (the set-up is overstated, the second half of the movie is yet another depiction of self-realization through contest). But Turbo has a little something extra, a little something you rarely see in any American movie, never mind an animated feature: Class consciousness.

But Turbo has a little something extra, a little something you rarely see in any American movie, never mind an animated feature: Class consciousness. The unofficial dividing line between the two halves is Van Nuys Boulevard, although there is one community west of the boulevard, Reseda, which is spiritually part of the East Valley.

The unofficial dividing line between the two halves is Van Nuys Boulevard, although there is one community west of the boulevard, Reseda, which is spiritually part of the East Valley. Hollywood almost invariably depicts working class situations as stifling or as full of condescendingly “colorful” characters who are, at heart, “the salt of the earth.” Turbo’s director and co-writer David Soren (long may he prosper) sees this class arena as a garden of individuality. Turbo’s kidnapper is partnered with his brother in the taco stand (which looks exactly like a typical L.A. stand) and his friends include a white hobby shop owner, a Latina owner of a garage, and the Korean owner of a nail salon. Each character (even the racing snails) has his or her own dramatic integrity. And though every being in the movie is comic, there is barely a whiff of condescension. They have nothing to do with either salt or earth.

Hollywood almost invariably depicts working class situations as stifling or as full of condescendingly “colorful” characters who are, at heart, “the salt of the earth.” Turbo’s director and co-writer David Soren (long may he prosper) sees this class arena as a garden of individuality. Turbo’s kidnapper is partnered with his brother in the taco stand (which looks exactly like a typical L.A. stand) and his friends include a white hobby shop owner, a Latina owner of a garage, and the Korean owner of a nail salon. Each character (even the racing snails) has his or her own dramatic integrity. And though every being in the movie is comic, there is barely a whiff of condescension. They have nothing to do with either salt or earth. This is pretty impressive stuff. Coming as part and parcel of a pretty good animated feature it gives rise to a hope that Hollywood might start to pay attention to who people really are and how they actually live.

This is pretty impressive stuff. Coming as part and parcel of a pretty good animated feature it gives rise to a hope that Hollywood might start to pay attention to who people really are and how they actually live.

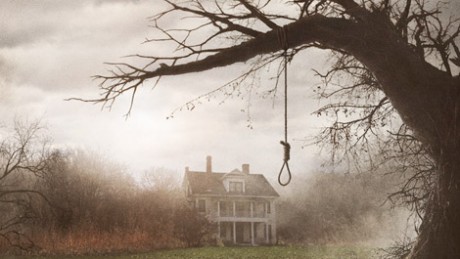

I wouldn’t mind taking ju st 15 inches with Byzantium. Not because it’s bad; on the contrary. But Jordan and screenwriter Moira Buffini have so crammed the movie with references to horror films and Gothic literature that it’s difficult tracking them all down, never mind exploring them. Frankly, I’ve found the process almost overwhelming. Although I’d already watched the movies or read the fiction that the movie invokes, I felt compelled to go back to it all for second (or third or fourth) looks. That still left Byzantium itself, shorn of references, to deal with.

I wouldn’t mind taking ju st 15 inches with Byzantium. Not because it’s bad; on the contrary. But Jordan and screenwriter Moira Buffini have so crammed the movie with references to horror films and Gothic literature that it’s difficult tracking them all down, never mind exploring them. Frankly, I’ve found the process almost overwhelming. Although I’d already watched the movies or read the fiction that the movie invokes, I felt compelled to go back to it all for second (or third or fourth) looks. That still left Byzantium itself, shorn of references, to deal with. Byzantium begins with Eleanor, who appears to be about 16 but who is actually more than 200, throwing notebook pages from a balcony down to the city street below. The pages contain, she says, a story no one can know, a story which turns out to be the tale of her life as a human and as a vampire. But down on the street, an old tramp grabs a page, reads it, and clearly understands it. The young/old girl and the old man find a basement room in which to talk and the old man speaks of the revenants he heard of as a boy and how he is tired of life and ready to die. Eleanor answers his implicit request by cutting a vein in his arm with her long, sharp thumbnail and drinking her petitioner’s blood until he dies. In doing so she reveals her nature and her character as a vampire who only drinks the blood of those who are tired of life. (In Byzantium, humans can only die from a vampire encounter; they aren’t turned into vampires themselves. In fact, no one can become a vampire who doesn’t desire it.)

Byzantium begins with Eleanor, who appears to be about 16 but who is actually more than 200, throwing notebook pages from a balcony down to the city street below. The pages contain, she says, a story no one can know, a story which turns out to be the tale of her life as a human and as a vampire. But down on the street, an old tramp grabs a page, reads it, and clearly understands it. The young/old girl and the old man find a basement room in which to talk and the old man speaks of the revenants he heard of as a boy and how he is tired of life and ready to die. Eleanor answers his implicit request by cutting a vein in his arm with her long, sharp thumbnail and drinking her petitioner’s blood until he dies. In doing so she reveals her nature and her character as a vampire who only drinks the blood of those who are tired of life. (In Byzantium, humans can only die from a vampire encounter; they aren’t turned into vampires themselves. In fact, no one can become a vampire who doesn’t desire it.) As the movie goes on – that is, “goes on” in the present and in 1804 – the female pair’s differing attitudes towards men quickly emerges. Clara had become a vampire as a consequence of being forced into prostitution by a brutish snob of an English cavalry officer. She makes men her prey, going the wholesale route by becoming madam of her own brothel where she can feast on the perversions and blood of johns. Eleanor has suffered at men’s hands, but not so dramatically as Clara and is able to take men as they come. She even begins a friendship/romance with a young man with a fatal blood disease whom she meets in a seaside town.

As the movie goes on – that is, “goes on” in the present and in 1804 – the female pair’s differing attitudes towards men quickly emerges. Clara had become a vampire as a consequence of being forced into prostitution by a brutish snob of an English cavalry officer. She makes men her prey, going the wholesale route by becoming madam of her own brothel where she can feast on the perversions and blood of johns. Eleanor has suffered at men’s hands, but not so dramatically as Clara and is able to take men as they come. She even begins a friendship/romance with a young man with a fatal blood disease whom she meets in a seaside town. Eleanor and Clara aren’t just hunters, though. They are also the hunted. For reasons that only gradually become clear, they are being hunted by some male vampires who want to extinguish their existence.

Eleanor and Clara aren’t just hunters, though. They are also the hunted. For reasons that only gradually become clear, they are being hunted by some male vampires who want to extinguish their existence. In Byzantium, Jordan keeps horror sequences to a minimum. Images are drained of bright color and nearly the only time you see red is when Eleanor or Clara wear a red item of clothing, as if that were the only way Jordan can bring himself to refer to vampirism. Even some blood-drinking scenes are equally discreet; one of Eleanor’s takes place entirely behind opaque glass. And in suspense or horror scenes, when other directors would resort to close-ups and quick cuts, Jordan keeps his camera distant and his cutting almost languorous.

In Byzantium, Jordan keeps horror sequences to a minimum. Images are drained of bright color and nearly the only time you see red is when Eleanor or Clara wear a red item of clothing, as if that were the only way Jordan can bring himself to refer to vampirism. Even some blood-drinking scenes are equally discreet; one of Eleanor’s takes place entirely behind opaque glass. And in suspense or horror scenes, when other directors would resort to close-ups and quick cuts, Jordan keeps his camera distant and his cutting almost languorous. At one point, we learn that Clara also uses the names Claire and, most significantly, Carmilla. Carmilla is the name of a character and novella written by the great Irish Gothic writer,

At one point, we learn that Clara also uses the names Claire and, most significantly, Carmilla. Carmilla is the name of a character and novella written by the great Irish Gothic writer, Jordan makes another reference near the movie’s midpoint when he shows an uninterested Eleanor sitting in front of a television playing the Hammer horror film, Dracula, Prince of Darkness. The movie was made in 1966, between Hammer’s first period, when it was making slightly lurid versions of classic horror tales, and its second, when it went all out on boobs-and-blood. Some of Hammer’s best productions were undertaken around these years and Prince of Darkness gets the studio’s top treatment, with typically ingenious direction from the studio’s busiest director, Terence Fisher.

Jordan makes another reference near the movie’s midpoint when he shows an uninterested Eleanor sitting in front of a television playing the Hammer horror film, Dracula, Prince of Darkness. The movie was made in 1966, between Hammer’s first period, when it was making slightly lurid versions of classic horror tales, and its second, when it went all out on boobs-and-blood. Some of Hammer’s best productions were undertaken around these years and Prince of Darkness gets the studio’s top treatment, with typically ingenious direction from the studio’s busiest director, Terence Fisher. The excerpted scene is a variation on a turning point from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1896): The destruction of Lucy Westenra. Lucy is an attractive young woman who is the first victim of the vampire count, turning into a vampire herself and feasting on children. As anyone who has read the scene knows, her destruction by a group of men sounds extraordinarily like a rape. The scene in the Hammer film echoes that gory episode, with a female vampire seized by men, roughly held down on a table, and hammered with a suitably phallic stake.

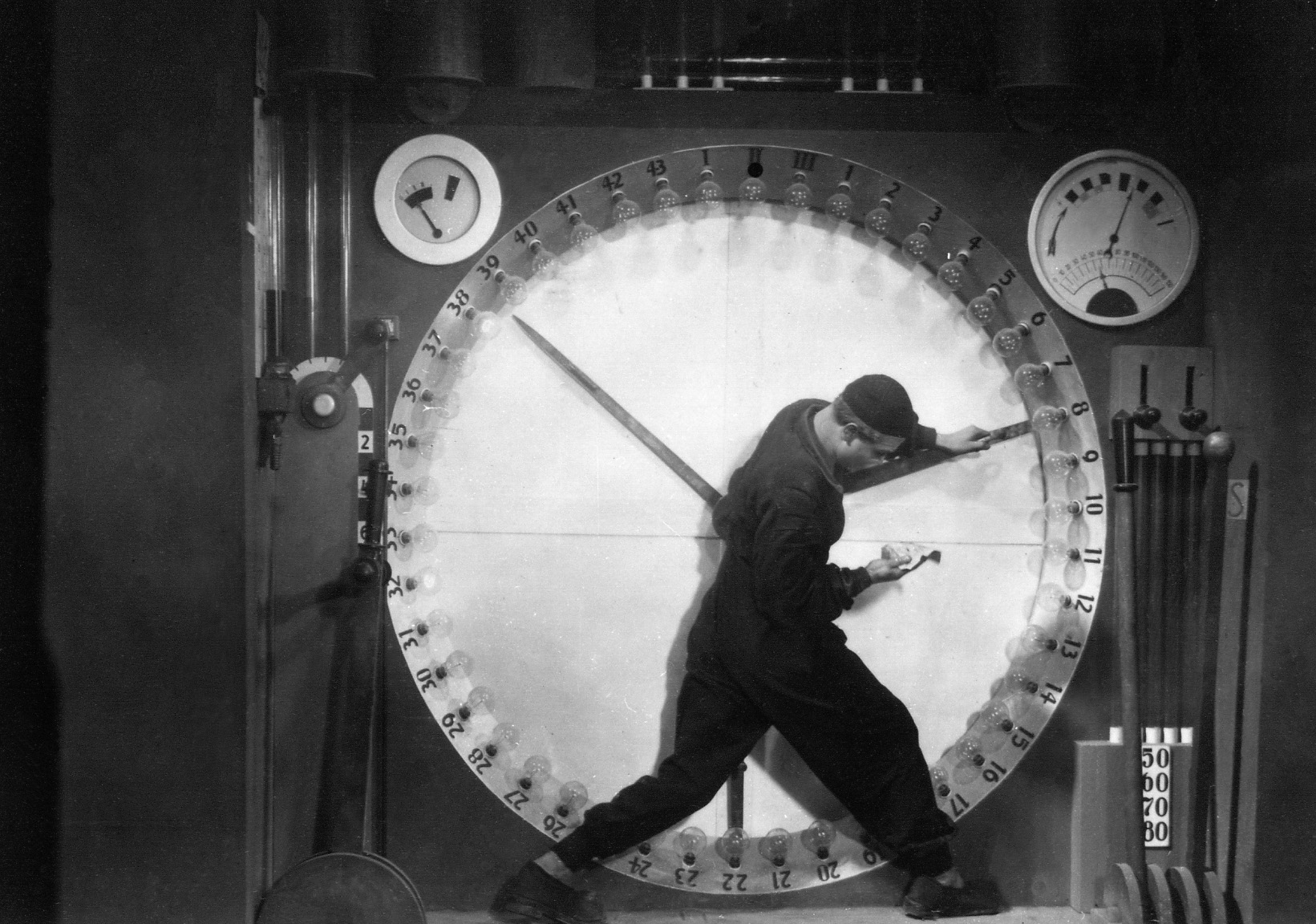

The excerpted scene is a variation on a turning point from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1896): The destruction of Lucy Westenra. Lucy is an attractive young woman who is the first victim of the vampire count, turning into a vampire herself and feasting on children. As anyone who has read the scene knows, her destruction by a group of men sounds extraordinarily like a rape. The scene in the Hammer film echoes that gory episode, with a female vampire seized by men, roughly held down on a table, and hammered with a suitably phallic stake. There is a famous cinematic vampire, of course, whose appearance recalls a witch more than a bloodsucker: That is the malevolent crone of Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931). The screenplay for that movie is based on a short story collection, In a Glass Darkly, by J. Sheridan Le Fanu. A collection which also included – why, Carmilla, of course.

There is a famous cinematic vampire, of course, whose appearance recalls a witch more than a bloodsucker: That is the malevolent crone of Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931). The screenplay for that movie is based on a short story collection, In a Glass Darkly, by J. Sheridan Le Fanu. A collection which also included – why, Carmilla, of course.