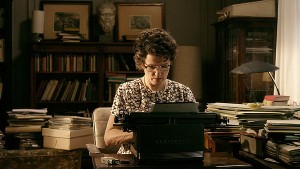

The first time I laughed at the new Woody Allen movie “Jasmine Blue” – and I must confess I have had only intermittent interest in his films (liked “Midnight in Paris,” skipped “To Rome With Love”) for a while and had no idea what the film was about – happened very early on. Later I realized that the gag, which was indeed funny at the time, or at least I wasn’t the only person laughing (which has been happening these days with increasing frequency) was, in retrospect, not funny at all.

To cite the difference between comedy and tragedy as defined in Allen’s “Crimes and Misdemeanors” (“If it bends, it’s comedy, if it breaks it’s tragedy” and “comedy is tragedy plus time”), this was tragedy. However, the scene inverts the other part of the definition, because this was a case of tragedy being comedy plus time.

I’m referring to when Jasmine (Cate Blanchett), disembarking a flight at the San Francisco airport, enthusiastically engages an elderly woman in a conversation, or rather a monologue, talking with intimate detail about her husband, her friends, her chi-chi lifestyle, dropping names and labels and price tags. They pick up their luggage (Jasmine’s is Louis Vuitton), the older woman’s husband arrives, they go their separate ways, and it becomes obvious that the woman is not an acquaintance of Jasmine, but a total stranger who had the misfortune of sitting next to this crazy person who, in lieu of talking to herself, has unloaded on her fellow passenger her whole delusional life history.

No more bending – it’s broken. And with that the laughter stops.

Jasmine, as the expertly wound and uncoiled exposition eventually establishes, had been married to Hal (Alec Baldwin), a Bernie Madoff-like high-stakes financial conman. After Hal got busted, Jasmine was left disgraced and penniless, and her husband’s fall also took with it the nest egg of Jasmine’s sister Ginger (Sally Hawkins) and Ginger’s husband Augie (Andrew Dice Clay),

in effect ending their marriage.

Now Jasmine is forced to seek a place to live with her sister in her meat-and-potatoes San Francisco apartment.

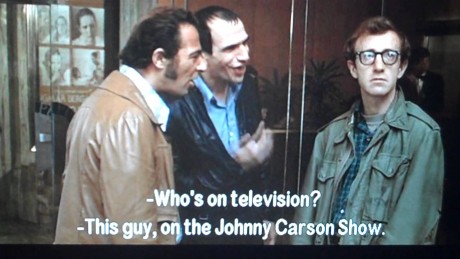

There she descends like a queen, in denial about her fall from the upper class, picky and bitchy and, Blanche Dubois-like, alienating Ginger’s new, Stanley Kowalski-like boyfriend Chili (Bobby Cannavale) – hey, why not throw in the “two guys named Cheech” from “Annie Hall?”

– who hates Jasmine’s undeserved sense of entitlement, her condescension and disapproval, her meddling, and her hoity-toity ways.

Yes, it’s A “Streetcar Named Desire.” But the theme of class and cultural differences has underscored many of Allen’s films, going back at least to his first “serious” movie, the pseudo-Bergmanesque-with-sidetrips-to-Chekhov “Interiors” (1978), in which the patriarch of a snooty waspy family dumps his brittle, joyless wife for a bubbly “vulgarian” – a long-in-the-tooth party girl. There are sister problems in that film, too.

Though “Blue Jasmine” draws on many such long-established Allen – not to mention Tennessee Williams – themes, it does break new ground. I’m not positive, but I think this is the first of his films that cleaves so intensely to one character’s point of view, to the extent that it is never altogether clear whether a sequence involves a flashback, a hallucination, or both.

A couple of notes about Blanchett’s performance. I would say that it is the best I have seen in any Allen film. Hypnotic, unrelenting, it inundates the screen with nuanced misery, anger, self-deception, unearned arrogance, snobbery, pathos, prickly resilience, petty resentment, deluded self-entitlement, and despair. And sweat. This is not a woman you should ask out on a date, even though Peter Sarsgaard’s slick and wealthy widower gives it a shot.

The portrayal affected me so much that by the end of the film I found myself sweating as much as Jasmine. Here’s an observation I have made about sweating actresses: the last non-American English-speaking actress who sweated this much, to the point of having visible half-moons of perspiration under her arms, was Tilda Swinton in “Michael Clayton” (2007).

She won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. I foresee a Best Actress nomination, at least, and possibly an Oscar for Blanchett, but she would probably have accomplished the same whether she was sweating or not.

Nonetheless, Blanchett’s tour-de-force performance has the paradoxical effect of concealing what it is that makes her character so crazy. She wraps the viewer so thoroughly in Jasmine’s unreliable point-o- view that the reasons for her downfall and ostracism are hard to figure. Since this is a tragedy, and Jasmine ostensibly is the tragic hero, what is her harmatia, her fatal flaw?

Is it the fact that she’s a snob? A compulsive liar? A narcissist incapable of empathy or self-awareness? In a state of constant denial? Is it simply because she enjoys the buzz from a couple of bottles of wine or three or four Stoli martinis and a dozen Xanaxes? And then there’s her poor judgment in men:

she sure knows how to pick them – both for herself and others, and when she actually finds a keeper, she doesn’t have the moral fiber or good sense to capitalize on it.

Maybe she’s simply guilty of denial, willfully blind to the failings and treachery of a man she idolizes. For in addition to bilking friends out of billions and cheating on his wife, Hal commits the unforgiveable offense of equating price tags with value, of adorning his property with artworks for which he has no appreciation except as status symbols.

Jasmine is no better. When you come down to it, her ultimate crime is that she has bad taste.

— Peter Keough

Johnnie To is the best action director in the world and one of the greatest of all time. Full stop, period, the end. Many people would agree because of his movies’ most obvious virtue: Flabbergasting cutting that, once the bullets start flying (and boy, do they fly), is faster then, well, a speeding bullet.

Johnnie To is the best action director in the world and one of the greatest of all time. Full stop, period, the end. Many people would agree because of his movies’ most obvious virtue: Flabbergasting cutting that, once the bullets start flying (and boy, do they fly), is faster then, well, a speeding bullet. To’s brilliance, which can seem boundless, includes defining action as its absence. Typically during a To action film (he also makes comedies, romances and period films), there comes a moment when the characters come to a complete standstill, with even their faces frozen into emotionless masks. But there is a tension here – emotional torque – the signals an oncoming sequence of utter mayhem. I’m not sure there is anyone else in the world who can wring so much from a shot of someone just sitting there.

To’s brilliance, which can seem boundless, includes defining action as its absence. Typically during a To action film (he also makes comedies, romances and period films), there comes a moment when the characters come to a complete standstill, with even their faces frozen into emotionless masks. But there is a tension here – emotional torque – the signals an oncoming sequence of utter mayhem. I’m not sure there is anyone else in the world who can wring so much from a shot of someone just sitting there. Drug War is set in one of those vast, Chinese urban centers, full of industrial sites and cruddy-looking apartment buildings; it makes you wonder what people are ultimately waging war over. Although compared to the drug gangs the police don’t appear to be particularly brutal, they’re not above beating prisoners or like behaviors.

Drug War is set in one of those vast, Chinese urban centers, full of industrial sites and cruddy-looking apartment buildings; it makes you wonder what people are ultimately waging war over. Although compared to the drug gangs the police don’t appear to be particularly brutal, they’re not above beating prisoners or like behaviors. Maybe Chinese bureaucrats didn’t want to get in the way of a good movie. Because that’s what To has come up with. No, let’s allow the superlatives to flow, because Drug War has earned them. It’s exciting and mind-blowing – brilliant.

Maybe Chinese bureaucrats didn’t want to get in the way of a good movie. Because that’s what To has come up with. No, let’s allow the superlatives to flow, because Drug War has earned them. It’s exciting and mind-blowing – brilliant.

Reviews of animated features generally format themselves and Turbo, the latest from DreamWorks Animation, is susceptible to the same treatment. First comes a plot description (a garden snail with a need for speed finds himself suddenly capable of high velocity), an assessment of the animation in general (good) and of the character animation (fair to very good). Then a list of shortcomings (the set-up is overstated, the second half of the movie is yet another depiction of self-realization through contest).

Reviews of animated features generally format themselves and Turbo, the latest from DreamWorks Animation, is susceptible to the same treatment. First comes a plot description (a garden snail with a need for speed finds himself suddenly capable of high velocity), an assessment of the animation in general (good) and of the character animation (fair to very good). Then a list of shortcomings (the set-up is overstated, the second half of the movie is yet another depiction of self-realization through contest). But Turbo has a little something extra, a little something you rarely see in any American movie, never mind an animated feature: Class consciousness.

But Turbo has a little something extra, a little something you rarely see in any American movie, never mind an animated feature: Class consciousness. The unofficial dividing line between the two halves is Van Nuys Boulevard, although there is one community west of the boulevard, Reseda, which is spiritually part of the East Valley.

The unofficial dividing line between the two halves is Van Nuys Boulevard, although there is one community west of the boulevard, Reseda, which is spiritually part of the East Valley. Hollywood almost invariably depicts working class situations as stifling or as full of condescendingly “colorful” characters who are, at heart, “the salt of the earth.” Turbo’s director and co-writer David Soren (long may he prosper) sees this class arena as a garden of individuality. Turbo’s kidnapper is partnered with his brother in the taco stand (which looks exactly like a typical L.A. stand) and his friends include a white hobby shop owner, a Latina owner of a garage, and the Korean owner of a nail salon. Each character (even the racing snails) has his or her own dramatic integrity. And though every being in the movie is comic, there is barely a whiff of condescension. They have nothing to do with either salt or earth.

Hollywood almost invariably depicts working class situations as stifling or as full of condescendingly “colorful” characters who are, at heart, “the salt of the earth.” Turbo’s director and co-writer David Soren (long may he prosper) sees this class arena as a garden of individuality. Turbo’s kidnapper is partnered with his brother in the taco stand (which looks exactly like a typical L.A. stand) and his friends include a white hobby shop owner, a Latina owner of a garage, and the Korean owner of a nail salon. Each character (even the racing snails) has his or her own dramatic integrity. And though every being in the movie is comic, there is barely a whiff of condescension. They have nothing to do with either salt or earth. This is pretty impressive stuff. Coming as part and parcel of a pretty good animated feature it gives rise to a hope that Hollywood might start to pay attention to who people really are and how they actually live.

This is pretty impressive stuff. Coming as part and parcel of a pretty good animated feature it gives rise to a hope that Hollywood might start to pay attention to who people really are and how they actually live.

I wouldn’t mind taking ju st 15 inches with Byzantium. Not because it’s bad; on the contrary. But Jordan and screenwriter Moira Buffini have so crammed the movie with references to horror films and Gothic literature that it’s difficult tracking them all down, never mind exploring them. Frankly, I’ve found the process almost overwhelming. Although I’d already watched the movies or read the fiction that the movie invokes, I felt compelled to go back to it all for second (or third or fourth) looks. That still left Byzantium itself, shorn of references, to deal with.

I wouldn’t mind taking ju st 15 inches with Byzantium. Not because it’s bad; on the contrary. But Jordan and screenwriter Moira Buffini have so crammed the movie with references to horror films and Gothic literature that it’s difficult tracking them all down, never mind exploring them. Frankly, I’ve found the process almost overwhelming. Although I’d already watched the movies or read the fiction that the movie invokes, I felt compelled to go back to it all for second (or third or fourth) looks. That still left Byzantium itself, shorn of references, to deal with. Byzantium begins with Eleanor, who appears to be about 16 but who is actually more than 200, throwing notebook pages from a balcony down to the city street below. The pages contain, she says, a story no one can know, a story which turns out to be the tale of her life as a human and as a vampire. But down on the street, an old tramp grabs a page, reads it, and clearly understands it. The young/old girl and the old man find a basement room in which to talk and the old man speaks of the revenants he heard of as a boy and how he is tired of life and ready to die. Eleanor answers his implicit request by cutting a vein in his arm with her long, sharp thumbnail and drinking her petitioner’s blood until he dies. In doing so she reveals her nature and her character as a vampire who only drinks the blood of those who are tired of life. (In Byzantium, humans can only die from a vampire encounter; they aren’t turned into vampires themselves. In fact, no one can become a vampire who doesn’t desire it.)

Byzantium begins with Eleanor, who appears to be about 16 but who is actually more than 200, throwing notebook pages from a balcony down to the city street below. The pages contain, she says, a story no one can know, a story which turns out to be the tale of her life as a human and as a vampire. But down on the street, an old tramp grabs a page, reads it, and clearly understands it. The young/old girl and the old man find a basement room in which to talk and the old man speaks of the revenants he heard of as a boy and how he is tired of life and ready to die. Eleanor answers his implicit request by cutting a vein in his arm with her long, sharp thumbnail and drinking her petitioner’s blood until he dies. In doing so she reveals her nature and her character as a vampire who only drinks the blood of those who are tired of life. (In Byzantium, humans can only die from a vampire encounter; they aren’t turned into vampires themselves. In fact, no one can become a vampire who doesn’t desire it.) As the movie goes on – that is, “goes on” in the present and in 1804 – the female pair’s differing attitudes towards men quickly emerges. Clara had become a vampire as a consequence of being forced into prostitution by a brutish snob of an English cavalry officer. She makes men her prey, going the wholesale route by becoming madam of her own brothel where she can feast on the perversions and blood of johns. Eleanor has suffered at men’s hands, but not so dramatically as Clara and is able to take men as they come. She even begins a friendship/romance with a young man with a fatal blood disease whom she meets in a seaside town.

As the movie goes on – that is, “goes on” in the present and in 1804 – the female pair’s differing attitudes towards men quickly emerges. Clara had become a vampire as a consequence of being forced into prostitution by a brutish snob of an English cavalry officer. She makes men her prey, going the wholesale route by becoming madam of her own brothel where she can feast on the perversions and blood of johns. Eleanor has suffered at men’s hands, but not so dramatically as Clara and is able to take men as they come. She even begins a friendship/romance with a young man with a fatal blood disease whom she meets in a seaside town. Eleanor and Clara aren’t just hunters, though. They are also the hunted. For reasons that only gradually become clear, they are being hunted by some male vampires who want to extinguish their existence.

Eleanor and Clara aren’t just hunters, though. They are also the hunted. For reasons that only gradually become clear, they are being hunted by some male vampires who want to extinguish their existence. In Byzantium, Jordan keeps horror sequences to a minimum. Images are drained of bright color and nearly the only time you see red is when Eleanor or Clara wear a red item of clothing, as if that were the only way Jordan can bring himself to refer to vampirism. Even some blood-drinking scenes are equally discreet; one of Eleanor’s takes place entirely behind opaque glass. And in suspense or horror scenes, when other directors would resort to close-ups and quick cuts, Jordan keeps his camera distant and his cutting almost languorous.

In Byzantium, Jordan keeps horror sequences to a minimum. Images are drained of bright color and nearly the only time you see red is when Eleanor or Clara wear a red item of clothing, as if that were the only way Jordan can bring himself to refer to vampirism. Even some blood-drinking scenes are equally discreet; one of Eleanor’s takes place entirely behind opaque glass. And in suspense or horror scenes, when other directors would resort to close-ups and quick cuts, Jordan keeps his camera distant and his cutting almost languorous. At one point, we learn that Clara also uses the names Claire and, most significantly, Carmilla. Carmilla is the name of a character and novella written by the great Irish Gothic writer,

At one point, we learn that Clara also uses the names Claire and, most significantly, Carmilla. Carmilla is the name of a character and novella written by the great Irish Gothic writer, Jordan makes another reference near the movie’s midpoint when he shows an uninterested Eleanor sitting in front of a television playing the Hammer horror film, Dracula, Prince of Darkness. The movie was made in 1966, between Hammer’s first period, when it was making slightly lurid versions of classic horror tales, and its second, when it went all out on boobs-and-blood. Some of Hammer’s best productions were undertaken around these years and Prince of Darkness gets the studio’s top treatment, with typically ingenious direction from the studio’s busiest director, Terence Fisher.

Jordan makes another reference near the movie’s midpoint when he shows an uninterested Eleanor sitting in front of a television playing the Hammer horror film, Dracula, Prince of Darkness. The movie was made in 1966, between Hammer’s first period, when it was making slightly lurid versions of classic horror tales, and its second, when it went all out on boobs-and-blood. Some of Hammer’s best productions were undertaken around these years and Prince of Darkness gets the studio’s top treatment, with typically ingenious direction from the studio’s busiest director, Terence Fisher. The excerpted scene is a variation on a turning point from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1896): The destruction of Lucy Westenra. Lucy is an attractive young woman who is the first victim of the vampire count, turning into a vampire herself and feasting on children. As anyone who has read the scene knows, her destruction by a group of men sounds extraordinarily like a rape. The scene in the Hammer film echoes that gory episode, with a female vampire seized by men, roughly held down on a table, and hammered with a suitably phallic stake.

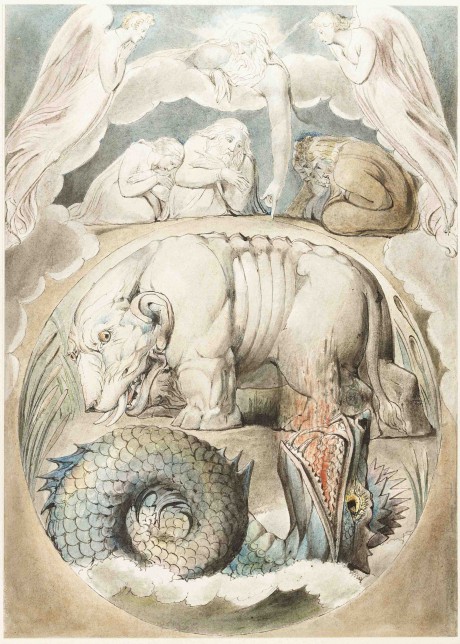

The excerpted scene is a variation on a turning point from Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1896): The destruction of Lucy Westenra. Lucy is an attractive young woman who is the first victim of the vampire count, turning into a vampire herself and feasting on children. As anyone who has read the scene knows, her destruction by a group of men sounds extraordinarily like a rape. The scene in the Hammer film echoes that gory episode, with a female vampire seized by men, roughly held down on a table, and hammered with a suitably phallic stake. There is a famous cinematic vampire, of course, whose appearance recalls a witch more than a bloodsucker: That is the malevolent crone of Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931). The screenplay for that movie is based on a short story collection, In a Glass Darkly, by J. Sheridan Le Fanu. A collection which also included – why, Carmilla, of course.

There is a famous cinematic vampire, of course, whose appearance recalls a witch more than a bloodsucker: That is the malevolent crone of Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931). The screenplay for that movie is based on a short story collection, In a Glass Darkly, by J. Sheridan Le Fanu. A collection which also included – why, Carmilla, of course.