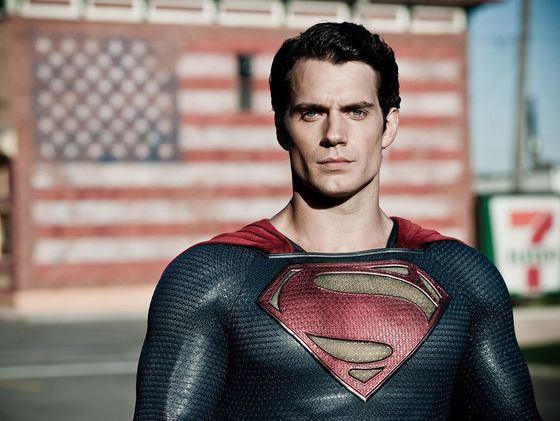

“You will be a god to them,” the dead but talkative Jor-el assures his son Kal-el, who is on the verge of manhood. “Them” refers to us pitiful humans, soon to be cowering behind the nascent Superman’s cape. We’ll need to cower because soon Earth will be under attack by the army of General Zod, an angry and well-armed refugee from the wrecked planet Krypton, which was also the home of the El family. Oh yes, weak and helpless as the people of Earth are, their pitiful lives will be in the hands of a powerful leader. Make that Leader.

“You will be a god to them,” the dead but talkative Jor-el assures his son Kal-el, who is on the verge of manhood. “Them” refers to us pitiful humans, soon to be cowering behind the nascent Superman’s cape. We’ll need to cower because soon Earth will be under attack by the army of General Zod, an angry and well-armed refugee from the wrecked planet Krypton, which was also the home of the El family. Oh yes, weak and helpless as the people of Earth are, their pitiful lives will be in the hands of a powerful leader. Make that Leader.

Peter traced the fractured line of Christian references in Man of Steel. Director Zack Snyder didn’t stop there; he’s also shoved shards of paganism. The very opening scene is set on craggy, mountainous Krypton, which is hours or days away from imploding. During an all-over-but-the-shouting session, the robed members of the planet council are listening to scientist Jor-el tut-tut them when in bursts Zod in Krypton’s update of ancient helmet and armor.

Zod is attempting a coup, as if he were Ares, the savage Greek god of war, facing down fellow Olympians. A special being, someone such as Herakles (who once bested Ares in battle), the offspring of Zeus and a mortal.

Everyone knows the rest of the story. The baby Kal-el is rocketed off to earth, where he lands in Kanasas and is raised by a pair of jes’ folks farmers, Ma and Pa Kent, who christen their space baby Clark. And so, Kal-el/Clark has mortal parents to go along with his immortal ones (Jor-el is killed early in the action, but this doesn’t keep him from reappearing throughout). And so forth, and so on.

This might have been nothing more than harmless and, under Snyder’s direction, meaningless template but for 20th-century history. Lo not so many years ago, it was fascism that evoked ancient pagan myth, for both ideological and ceremonial exploitation. Hitler was a Teutonic Herakles, an offspring of mortals (Austria) until he recognized his true, divine parents (the Eternal Reich), who emerged from among the people but soared above him (see the opening of Triumph of the Will). It has been the generational project of comic book creators and filmmakers to somehow treat their characters “mythic,” a turn that leads them into traps like V for Vendetta, a putatively anti-fascist film that was utterly fascist itself.

This might have been nothing more than harmless and, under Snyder’s direction, meaningless template but for 20th-century history. Lo not so many years ago, it was fascism that evoked ancient pagan myth, for both ideological and ceremonial exploitation. Hitler was a Teutonic Herakles, an offspring of mortals (Austria) until he recognized his true, divine parents (the Eternal Reich), who emerged from among the people but soared above him (see the opening of Triumph of the Will). It has been the generational project of comic book creators and filmmakers to somehow treat their characters “mythic,” a turn that leads them into traps like V for Vendetta, a putatively anti-fascist film that was utterly fascist itself.

Their predecessors who were pleased to make their work as childish as possible and to do that self-consciously. The primal joys of a child gaining new strength and maturity went all the way towards keeping the stories universal and, hence, non-fascist.

Man of Steel might have offered some pleasant escapism of its own if it didn’t take its emotional cues from the pouty Kal/Clark/Superman. As the ever-growing legion of superhero movies demonstrates, adolescent sulking isn’t exactly a mood lifter. Sam Raimi, who directed the Spider-Man movies starring Tobey Maguire, was able to leaven the teenage angst with humor and romance; compare that with the dismal mood of The Amazing Spider-Man of 2012. Man of Steel has a can’t-miss romantic opportunity in the person of Lois Lane which turns out not to be “can’t-miss” after all. Superman’s guiding response to life is resentment, the source of political reaction.

Man of Steel might have offered some pleasant escapism of its own if it didn’t take its emotional cues from the pouty Kal/Clark/Superman. As the ever-growing legion of superhero movies demonstrates, adolescent sulking isn’t exactly a mood lifter. Sam Raimi, who directed the Spider-Man movies starring Tobey Maguire, was able to leaven the teenage angst with humor and romance; compare that with the dismal mood of The Amazing Spider-Man of 2012. Man of Steel has a can’t-miss romantic opportunity in the person of Lois Lane which turns out not to be “can’t-miss” after all. Superman’s guiding response to life is resentment, the source of political reaction.

Snyder is hung up on conflicting desires to make a full-out effects action picture and a movie that “means” something. He ends up in control of neither. Like Superman himself, the action scenes surpass human scale, but similarly without a saving exuberance. When young Superman learns to fly, the emotional tone is less a joyful, “I can fly!” than an unappeased “I told you I could fly, but oh no, you didn’t believe me…” When he fights, it’s at the cost of hundreds of human lives. They are the sacrifice for his heroics. And Man of Steel is a holdover of the death cult we thought had been buried nearly 70 years ago.

–Henry Sheehan