Frank Tashlin was a rare example of an animator who made a successful switch from directing drawings to directing live action. Justifiably, much has been made of his habit of staging action with the nutty freedom from physics that are routine in cartoons but generally absent from movies. That liberating madness is captured in a line Bob Hope shouts out in Tashlin’s second feature, Son of Paleface (1952): “Hurry up – this is impossible!”

Tashlin’s contortions of the laws of the universe weren’t his only borrowings from animation. He also translated cartoon backgrounds into feature language. Tashlin worked at Warner Bros., where stingy budgets prevented any experiments with the illusion of three dimensions. Stuck with flat backgrounds, the Warner animators responded by using broad swatches of color and strict geometric forms to replace naturalistic scenery. Tashlin kept doing that when he turned to features, whether he could use the sharp brilliance of Technicolor or was stuck with smudgy, bleary “Color by Deluxe.”

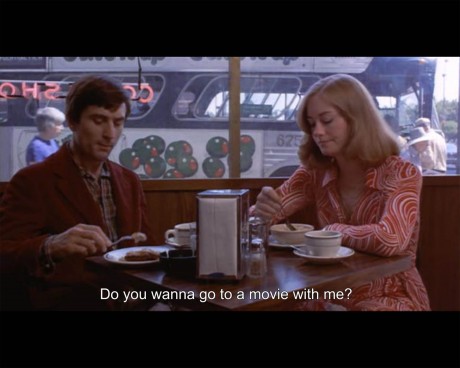

That’s pretty much what Pedro Almodόvar does with the background of the main set in I’m So Excited, the first class section of an airliner cabin. The set-up involves a full complement of crew and passengers stuck circling for hours in Spanish airspace after the discovery of a mechanical clitch. Having ingeniously trapped a large cast in a small space, Almodόvar sets in motion the cartoon version of a telenova, with extravagant romantic and sexual complications built on the already baroque designs of a flamboyant cast of characters.

The problem is that caricaturing a telenova is the same as sending up a Bond film: How do you send up a send up or – as here – caricature a cartoon? Almodόvar does as well as can be expected, though he produces an amusing comedy rather than the gut-buster he seems to have had in mind (occasionally you can note the mini-beats he’s built into dialogue to accommodate anticipated yuks from the audience).

The problem is that caricaturing a telenova is the same as sending up a Bond film: How do you send up a send up or – as here – caricature a cartoon? Almodόvar does as well as can be expected, though he produces an amusing comedy rather than the gut-buster he seems to have had in mind (occasionally you can note the mini-beats he’s built into dialogue to accommodate anticipated yuks from the audience).

But this brings us back to Warner cartoons, which were built around the lifelong struggle between the id and the superego. In his few outright comedies and undoubtedly in his dreams, Almodόvar constructs a world where the id always triumphs and always with happy consequences (id doesn’t necessarily translate to sex; there are repressive, though acted-on, sexual relationships in nearly all his films, especially over the last decade).

The Warner animators could depict these fights and consequent transformations literally, even to the point of distorting a character’s shape. Tashlin, especially when he worked with Jerry Lewis, managed to do the same thing with live action. Almodόvar’s movies and Tashlin’s exhibit different sorts of genius and so Almodόvar responds to the cartoon challenge with hair styles, costumes, make-up and behavioral tics. It’s not as big a laugh-getter as Tashlin’s style, but it is an effective means of expression.

The Warner animators could depict these fights and consequent transformations literally, even to the point of distorting a character’s shape. Tashlin, especially when he worked with Jerry Lewis, managed to do the same thing with live action. Almodόvar’s movies and Tashlin’s exhibit different sorts of genius and so Almodόvar responds to the cartoon challenge with hair styles, costumes, make-up and behavioral tics. It’s not as big a laugh-getter as Tashlin’s style, but it is an effective means of expression.

I’m So Excited is, thus, a must-see for Almodόvar aficionados and for the curious, but not for those who simply want a burlesque with a Spanish accent.

–Henry Sheehan