More than most superheroes – and believe me this is saying a lot because some of them have very involved origins and back stories – the Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), a.k.a. Logan, has a lot going on. At the beginning of his second solo movie he’s in a deep hole

in a Japanese POW camp in Nagasaki. Just as the A-bomb is about to go off,

he saves the life of a Japanese officer (Ken Yamamura).

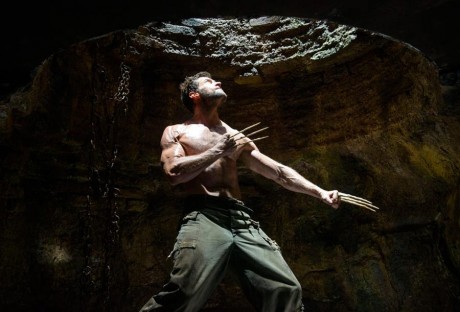

Huh? Where is this coming from? Then it turns out it’s just a dream, and when he wakes up Logan is in bed with Jean Grey, the mutant telepath, talking about life and death and love and loss – call it “Nagasaki, Mon Amour.” But didn’t she die in “X2: X-Men United” (2003)? Only to be reincarnated in “X-Men: the Last Stand” (2006) as her evil double Phoenix and then killed again? And did Wolverine and Jean really have anything going on between them? I thought she was Cyclops’s old lady. But then Logan wakes up again and he’s living in a cave in Alaska with a bottle of whiskey and a transistor radio. No wonder he can’t sleep. Or is he still sleeping?

In fact, although the narrative in this first part of the movie pops back and forth like one of those teleporting mutants, it’s very disjointedness somehow placates the need for coherence and continuity and achieves a kind of poetry. The Nagasaki sequence, for example, evokes the stark end-of the-world beauty of a similar scene in Spielberg’s “Empire of the Sun” (1987).

And the tête-à-têtes with the ghostly Grey, which recur like an irrepressible death wish, add an existential depth to the whole film despite its constant clutter of incident, explanation, and contrivance.

And that’s the theme, then – whether eternal life is a good idea. Cursed or blessed by a mutation that allows him to heal instantly, plus a skeleton of “adamantine” that is indestructible, Logan can live forever. So as explained in part in “X-Men Origins: Wolverine” (2009), Logan has been sulking and fighting lost causes and killing people in various conflicts for over 250 years, hence his cameo at Nagasaki at the beginning of the film. But if life has no end does it have any meaning? It makes Logan feel weary. I totally sympathize. Just trying to figure out what’s going in this movie is making me weary.

And so he chooses to spend his infinite remaining days a boozy hermit whose sole companion appears to be a giant bear (which looks unfortunately like the one in “The Golden Compass”) and whose recreation consists of occasionally pinning a bow hunter’s hand to a bar with his own arrow. That is, until Yukio (Rila Fukushima), a lethal, sword-wielding moppet in a schoolgirl outfit, shows up to bring him to Japan, where old Yashida, (Haruhiko Yamanouchi), the officer he saved at Nagasaki and now the wealthiest man in Asia, is dying, and wants to say goodbye, and thanks.

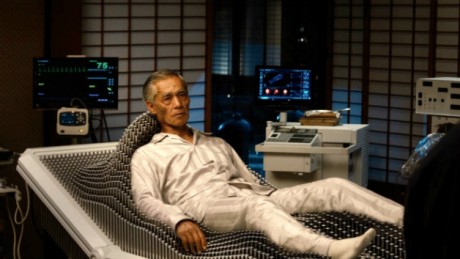

Or so he says. Turns out that Yashida is that rarity, a cowardly samurai. Having been saved once, he doesn’t want to face the prospect of dying again. So like the moribund, trillionaire CEO of the Weyland Corporation in “Prometheus” (2012), he will do anything within his almost infinite financial means to gain eternal life, including sucking out the immortality mutation from his old pal Logan, and applying it to himself.

And that’s just the start of Logan’s problems. He ends up protecting Yashida’s daughter Mariko (Tao Okamoto) from kidnappers, and soon everybody is out to get him for some reason or other – the Yakuza, a battalion of Ninjas, a dragon-lady mutant called Viper (Svetlana Khodchenkova), the ghost of Jean Grey… The police are after him, too, but they are inconsequential. As Mariko says, the government in Japan is so weak that gangsters now run everything. (Is that true? I’ve been too distracted by coverage of the royal birth to follow any other international news.) Other than that dubious observation, however, “The Wolverine,” unlike other films in the X-Men series, lacks much in the way of topical relevance.

I guess it is striving more for mythic significance, and, of course, spectacular action. A long sequence of hand-to-claw fighting on the roof of a bullet train speeding at 200 mph will hold your attention. But most of the battle scenes seem drawn from the Japanese “chambara,” or samurai film tradition, and Logan indeed refers to himself as a “ronin,” or masterless samurai. In one sequence, Logan takes on the ninja army and he’s pierced by countless arrows,

resembling Toshiro Mifune at the end of Akira Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood” (1957).

The arrows here are attached to cords, adding a weird, spidery, Gulliver-tied-up-by-the Lilliputians element to the image, as if each of Logan’s crimes of passion and violent follies were finally catching up to him and sticking to him and entangling him inescapably in his karma.

I don’t like throwing the word “karma” around, but here it is appropriate, as, in a Buddhist sense, Logan embodies the condition of a soul reborn too many times, burdened with too much grief and guilt and loss. He seeks the end of pain and desire — Nirvana – which may be what the recurring image of Jean Grey is offering him.

But Logan fights on, in ceaseless battles with innumerable assailants for an obscure cause. His fate resembles that of the rogue samurai in Kihachi Okamoto’s “The Sword of Doom” (1966), whose misdeeds finally catch up to him and who ends up fighting an eternal battle against endless adversaries, some real, some phantoms, in a tea house turned into a rice-paper-sliding-door hell.

That film ends on a freeze-frame of the swordsman in mid-stroke. In fact, the film had been intended as the first of a series. Indeed, there was plenty of material, as the novel it was based on by Kaizan Nakazato was, at 40 volumes, the longest in Japanese literature. I’m sure the X-Men series has, over its near half century run, grown to at least that size. It doesn’t look like Logan will be released from the cycle of suffering and rebirth any time soon.

— Peter Keough