“ – The feelings excited by improper art are kinetic, desire or loathing. Desire urges us to possess, to go to something; loathing urges us to abandon, to go from something. These are kinetic emotions. The arts which excite them, pornographical or didactic, are therefore improper arts. The esthetic emotion (I use the general term) is therefore static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing.”

James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Not that Joyce had a problem with pornography or didacticism. They might be “improper,” but they are still “art.”

When it came to porn, he was no prude. Not only did he write filthy love letters to his wife Nora, but in 1933 his masterpiece Ulysses was arraigned in a New York Southern District Federal Court (United States v. One Book Called Ulysses) before Judge John Munro Woolsey on charges of obscenity (in a landmark decision, Woolsey, an enlightened jurist and not a bad literary critic, explained why the book wasn’t pornographic.)

And as for didacticism, you can’t get much more didactic than does Stephen Dedalus in the multi-page discourse on Thomistic aesthetics quoted in part above.

Therefore it is a qualification and not a condemnation to say that, by the above definition, 12 Years a Slave, Steve McQueen’s adaptation of a 1852 memoir by Solomon Northup, a free man kidnapped and sold to slave owners, and Blue Is the Warmest Color, a chronicle of a lesbian love affair directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, fall into the category of “improper art.”

But for many people, they pass for masterpieces. Both films have swept awards from just about every critics society and are en route to likely triumphs at the Academy Awards. What can Joyce offer to counter such an overwhelming movement to canonize these pictures as masterpieces?

Let’s take the case of 12 Years a Slave. In it, the mind is not “arrested and raised above desire and loathing.” Quite the opposite. Nor is it that its intention. It is a didactic screed, a potent piece of propaganda, powerfully belaboring the message that the institution of slavery was an abomination, a debasement not only of the enslaved but also of those who enslaved them. And as such it succeeds with brutal, manipulative effectiveness.

For myself, by the end of the first hour, with over eight years as a slave still to go, after repeated whippings and cruelties and humiliations, I was fully convinced that slavery was a terrible thing, as I had been before I saw the movie. Ante-bellum slave traders, morally degenerate Southern plantation owners, pitiful liberal milksops who regarded the system with distaste while profiting from it, seeming sympathizers who prove to be inevitably treacherous, and sadistic white trash overseers like the guy played by Paul Dano

(who, though a talented actor, has unfortunately been typecast as loathsome characters of one sort or another), were all, without question , horrible human beings

Truth be told, I wanted to kill them. Exterminate the brutes!” Trouble is, those people have been dead for over a century. So it’s pointless, and inconsequential, to hate them, because they no longer exist.

On the other hand, their legacy obviously endures. But here again I don’t think the film will make much of an impact when it comes to the racism and injustice that prevails to the present day.

Those who already feel guilt and shame and anger about these things will feel the same way. But those who might actually learn something from the movie — say, Duck Dynasty patriarch Phil Robertson, noted among other things for declaring that black folks were better off singing in the cotton fields before thy got all uppity with that Civil Rights stuff; or Robertson’s politically opportunistic enablers such as Sarah Palin, Newt Gingrich, Ted Cruz — well, you won’t find them lining up at the Cineplex to buy tickets to see 12 Years a Slave.

But for those who do see the movie,although it won’t change their opinions, it might make them feel better about themselves. It offers scapegoats to take the blame for all the bad stuff we feel guilty about. Michael Fassbender’s psychopathic plantation owner is a perfect example:

now there’s someone you love to loathe. Forget that those who owned slaves back then included such enlightened American heroes as Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. That just makes things too complicated. It’s much more clarifying to pretend that they were all wicked and beyond the pale. This tactic is the essence of that sinister offshoot of didacticism, propaganda: create a demonic “other” who will take on our sins and serve as a despised projection of our guilt and rage,

In his “Contrarian View” of 12 Years a Slave posted on the Artsfuse website, Gerald Peary suggests that Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012) might, in fact, offer a more effective and legitimate approach to resolving such conflicted feelings. At first glance, this notion seems absurd, if not blasphemous: how can Tarantino’s absurdly violent, wish fulfillment fantasy be considered in the same context as McQueen’s earnest depiction of an actual historical nightmare?

Well, for a couple of reasons. For one, the hero of Django is not a passive victim rescued by the kindness of a white stranger

(a carpenter, no less – and note the cruciform framework in the background in this still from the film). That may well have been what really happened, but Northup’s actual revenge, the writing of the book on which the film is based, and his subsequent activism on behalf of the abolitionist cause, is mentioned only as an afterward.

In contrast, Django is no victim: he’s a juggernaut of vengeance who kills white people.

Lots of them.

“Am I alone (perhaps),” Peary asks, “in preferring, as a screen hero, Jamie Foxx’s rowdy, impolitic Django to [Chiwetol] Ejiofor’s impeccably behaved Northup?”

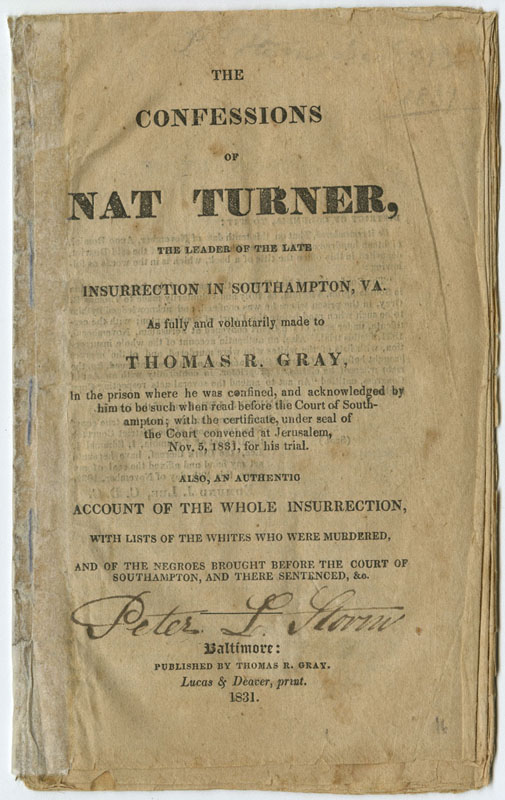

And if not the fictional character Django, why not another historical figure? Why not, as Peary suggests, someone like Nat Turner? Why has no movie been made about this leader of a bloody, failed slave uprising in Virginia in 1831?

Like Northop, Turner also wrote a book about his ordeal – as told to his lawyer Thomas Ruffin Gray

– and it was fictionalized by William Styron in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1967 novel The Confessions of Nat Turner. Perhaps that story is too complex, too hard to compartmentalize into facile categories of good and evil. Too tragic.

And while we’re on the subject, is it wrong to prefer a complex, comprehensible, even seductive villain as opposed to the cartoon monsters in 12 Years? Someone like the malevolent plantation owner played by Leonardo DiCaprio in Django, a diabolical villain with a certain joie de vivre, a nihilistic charm, someone who arouses not just loathing, but also terror, awe, even pity?

But to do so is to invite the condemnation of those who think that such reprobates should not be depicted as in any way remotely human like ourselves, but only as alien and demonic. They see any attempt to comprehend these fiends as an endorsement of the evil they have perpetrated.

That’s what Kathryn Bigelow learned to her regret when she depicted the CIA agents who inflicted grotesque, almost unwatchable torture on naked, chained and masked victims in her film Zero Dark Thirty (2012) . Other than that, however, they seemed kind of normal. They worried about their jobs, told jokes, were nice to their friends, and believed in the validity of what they were doing. Bigelow defended her non-didactic approach to this complex and ambiguous evil by insisting that depiction was not endorsement. To no avail.

More recently, Martin Scorsese has faced similar heat for his The Wolf of Wall Street. Some condemn it for glorifying the excesses of a generation of narcissistic sociopaths who lived an exotic (if tasteless) Satyricon-like life while destroying the economy and millions of lives. But Scorsese is attempting something more insidious than flat out condemnation; instead, he seduces the viewer into the attractions of a forbidden, alluring life style, itself a hallucinogenic version of the American Dream, in order to show that evil comes not from the pathology of a few, but from the sickness of a culture.

For these admirable intentions, as was the case with Bigelow, Scorsese can kiss his Oscar chances goodbye.

It may be some consolation to him and Bigelow and Tarantino that they are fulfilling James Joyce’s definition of “proper art.” They seek to elevate the soul to a level of aesthetic contemplation that induces a profound perception of good and evil and of human fate.

It is the essence of tragedy, as Stephen Dedalus points out in another of his aesthetic musings in Portrait of the Artist. Referring to the familiar Aristotlean formula that tragedy arouses pity and terror in order to produce in the audience a catharsis of those emotions, he adds:

“Aristotle has not defined pity and terror. I have…

“Pity is the feeling which arrests the mind in the presence of whatever is grave and constant in human suffering and unites it with the human sufferer. Terror is the feeling which arrests the mind in the presence of whatsoever is grave and constant in human sufferings and unites it with the secret cause.”

Pity and terror might not be as easy to take as an invigorating dose of desire or loathing. But in the long run they are more rewarding, and enduring.

NEXT: part two: pornography and Blue Is the Warmest Color