A 2009 interview with Lars von Trier on Antichrist

A 2009 interview with Lars von Trier on Antichrist

Writing a preview of a Lars von Trier retrospective (there is one scheduled for Feb. 1 at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, in preparation no doubt for the upcoming Nymphomaniac onslaught) and taking another look at his movies can get you down and – I don’t recommend watching, for example, the entire “Europa” trilogy in a single sitting – but in my research I came up with this lighthearted conversation I had (via Skype) with the director in 2009 about Antichrist. And in a sense that film sounds like it could be a precursor or prototype of the new project, with both starring a long-suffering Charlotte Gainsbourg.

Though some might find the discussion Of Willem Dafoe’s penis of greater interest, for me the best part is when my then editor of the late Boston Phoenix stepped into the conference room where the interview was taking place and, glancing into the laptop screen, cheerily asked me what video I was watching. I could see in von Trier’s spontaneous look of panic and terror that the man’s mental distress and instability, at least at this moment, was unfeigned.

PK: Hi! Thanks for fitting us into your schedule. How are you doing today?

LV: I’m actually okay. Today is an okay day.

PK: That’s good. It’s hit or miss, huh?

LV: (laughs) Yeah, sometimes.

PK: Would you recommend making a movie like this as a treatment for depression?

LV: Uh, yeah, well my treatment was more the work than the subject, if you understand what I mean. Just to get out of bed and do something. So, yeah I think I would recommend it. I don’t know how many people have the opportunity, you know, to do a film to get cured. There would be a lot of films made.

PK: I bet, yeah. It’s better than Prozac, though, I imagine.

LV: Yeah, Prozac is also good. But the problem about Prozac is it doesn’t continue being good, you know? It holds for a couple of years.

PK: Yeah. Well, um, it seems like the subject of the film also is like conducive to treating depression. Like the “He” character, the film sort of confronts things that are terrifying and tries to make them less terrifying. Is that correct?

LV: Yeah, the idea is normally when you panic, then your thoughts never get to your brain. You know, you panic before you think. And the idea is to think as soon as possible and then say to yourself, “Last time this happened, I was okay after a while so maybe I will be okay again after a while.”

PK: So that’s the therapy that the William Dafoe character is trying to apply to his wife and his mother.

LV: Yes, yes.

PK: And are you trying to like, confront the things that terrify you by making this movie?

LV: Yes, I am trying to. It’s easier said than done, you know. The end goal is of course confront the full anxiety, and you know, get all the way over. Because anxiety will, cannot heal itself within half an hour or how much, but it’s a painful half an hour. I don’t know if you know, if you have anxieties yourself.

PK: Absolutely none. Would you say that you’re more depressed with the aftermath and the response to the film? Has that made you depressed also?

LV: No, no, no, no. I’m fine with…you know, as I see it, some people like the film, some people don’t. That is fine; I’m not trying to make a very broad film as you might know if you’ve seen other stuff I’ve done. No, no, it’s fine. And it helped to get out, you know, I’m out of bed at the moment. So no, I’m quite content. So now the only problem is I’m supposed, or people would like to see me make another film, or some people would. So that’s what I’m working on.

PK: It seems like your new film is Planet Melancholia, is that correct?

LV: Yeah, it’s, we call the film Melancholia even though there’s a lot of other films with the same title. And it’s with planets.

PK: The film is dedicated to Tarkovsky; is the upcoming film kind of like Tarkovsky’s Solaris?

LV: Um, well, I’m very very fond of Tarkovsky, especially The Mirror, I don’t know if you’ve seen that? But certain films I like very much. I think he became a little bit weaker when he came to Western Europe. But Solaris is also a favorite of mine; I just re-saw a little of it again, yeah. If there’s a film I would have liked to have made, it would have been Solaris, yes.

PK: Is the planet Melancholia a happier place than Eden [the cabin where the couple in Antichrist goes for the depression cure]?

LV: (laughs) I’m afraid there are no really happy places in my films. You know, Planet Melancholia is a black planet, which it had to be for it to be very close to Earth without being detected. It’s a long story. It’s not a happier place. I wouldn’t recommend you go to Planet Melancholia.

PK: Antichrist reminded me of other films that you’ve done, like Medea. This seems to be an alternative version of that earlier film.

LV: Yeah, I’m not very fond of Medea, the way I did it. But that’s interesting. Maybe you can compare it because what you were seeing—nature, photography, in both of them, and we used nature quite a lot. But the Medea I did was from a script by Carl Dreyer. No, it’s not my favorite.

PK: Sorry to bring it up. But the theme of the woman who is wronged by a very sort of calculating man, and then responds in a very violent way, seems similar to the one in this film.

LV: I can see that. I have thought about it.

PK: Are you tired of people asking about misogyny?

LV: No. My one problem is that it’s so difficult to pronounce that I try to get around the word, you know?

I might have said this before, but it’s like kind of deciding to hate elephants. That’s kind of ridiculous, you know. You can hate one elephant that’s after you, but hating elephants in general is kind of a dumb. No, I made many films with women and about women so, no. Yeah, people tend to ask me.

PK: I thought your best response to that question was that you identify with the woman characters in your films.

LV: I think that is right. I think that the female characters in my film are more believable than the male characters.The male characters just tend to be idiots, all of them doing something completely wrong. And whereas the women just tend to follow their nature somehow.

PK: William Dafoe, and I think you’ve mentioned this in another interview, is probably the worst therapist in the history of movies. How would you advise him to treat the Charlotte Gainsbourg character, and what does he do wrong?

LV: Yeah, first of all, I have been undergoing this cognitive therapy for three years, and it’s I think it’s quite typical for me to be sarcastic about the subject. You can say that one of the main ideas behind any treatment like this is that a fear is a thought, and, you know, it doesn’t change reality. But you can say that in the film that it has changed reality.

But I wouldn’t let him treat her in any other way than with his dick, he has an enormous dick. He’s extremely well-equipped. And we had to kind of take the scenes out of the film, we had a stand-in for him, we had to take the scenes out with his own dick.

PK: Hold on: you had a stand-in dick? You had to have a stand-in dick for Dafoe?

LV: Yes, yes, we had to have, because Will’s own was too big.

PK: Too big to fit on the screen?

LV: (laughs) No, too big because everybody got very confused when they saw it.

PK: When he ejaculates blood, that was uh—

LV: Oh yeah, yeah. That was the double.

PK: It’s quite a trick.

LV: Uh, yes.

PK: Did you have a stand-in for Charlotte and her editing scene, her snipping scene.

LV: Yes, we also had a stand-in for that. Otherwise we could only do it once.

PK: You used some sort of prosthetic, I imagine, for that scene.

LV: Yeah, let’s say that, yes.

PK: One thing that strikes me about the film, what I find more disturbing maybe than the genital mutilation, is the attitude that existence itself is evil. Do you think that’s true?

LV: Yes, I believe I do. The idea for the film came after I had seen a film about the original forests of Europe and I found out, maybe you read this somewhere before, you know this image we all have of this fantastic, romantic place in a forest. But it is actually the image of the place that represents ultimate pain and struggle. If you go to a park, there’s not so much struggle. In this original forest there’s kind of the maximum of life and death. I thought that was quite interesting that I would also, if I had to think of a very good place where I had no fears, and so on, I would go to a place like this. But then, on the other hand, knowing that this was in fact a place full of all this suffering.

PK: In fairy tales, though, generally the characters are warned not to go into the forest, for good reason apparently.

LV: But that is because again, I think the forest kind of represents nature, and nature is always, sexuality is also, I believe, nature has always in fairy tales been seen, I think, as dangerous.

PK: But the word “nature” comes from the Latin word to be born. Is this film kind of a statement against reproduction?

LV: (laughs) No. Actually it’s not so much, it’s not a statement at all, I would say. I don’t make statements…

PK: It’s kind of an allegory. It seems like a number of your films lately have been allegorical, which is sometimes used as a derogatory term, but I think that it’s more of an allegory in the manner of Dante’s Divine Comedy or something like that. Do you see yourself as an allegorist? A religious allegorist?

LV: (laughs) No, no. I don’t see myself as anything. No, I do not see myself or the film, I try not to analyze, you know, what I’m doing, or the film. I try to make films instinctively, if there’s such a word, or intuitively. The films that I really like are, yeah, of course you can see anything as symbolism, but, yeah, intuitive and chaotic. The more a film seems to come in a natural way, or I would say, the less mathematics you can see in a film, and the less, also, symbols, because I think symbols are fine when you see a film, but symbols are not so interesting to use when you write it. So symbols I think are a waste of time.

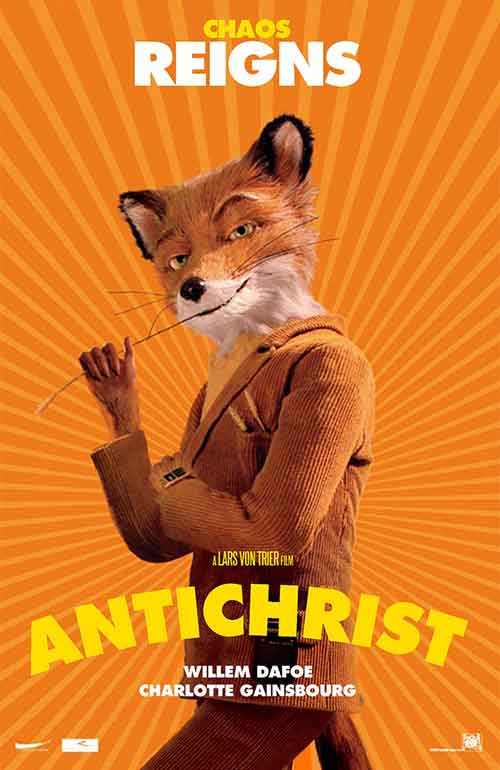

PK: The fox I heard came to you in a shamanistic journey? Is that true?

LV: (laughs) that’s right. Yes, I did from time to time these shamanistic things. It’s a very long story, but it had to do with a lady from my family who was in the hospital, and was dying, and then I read somewhere that through these shamans in the tribes, they could kind of travel for another person. And that is what I did for my family member, and she was very fond of foxes. So I went to talk to some foxes. And then there was this interesting thing that was not in the film, and that is that the first fox, yeah, the first fox I met behaved like this one.

PK: So this is when you’re in the trance.

LV: That’s right. There’s a strong sound that you kind of go into a trance from. And then this fox was like in the film, but afterwards, I met some other foxes, and they said, one thing that was quite interesting was that they said “never trust the first fox you meet.”

PK: Which was the one that says, “chaos reigns,” right? So which fox do you trust?

LV: (laughs) I trust the one with the chaos.

PK: Do you know that that phrase is becoming a kind of catch-phrase, popular among people online, and so forth?

LV: Yes. I saw something on YouTube that looked very funny, yes. Great.

PK: Somebody online also suggested that you could market the three beggars as toys. Has anything like that ever occurred to you? Like having merchandised figures out of those creatures, of the three beggars, the fox and the deer, and the—is it a raven or a crow?

LV: Yeah it is supposed to be a crow but we could only get a raven. (laughs)

PK: Yeah. Edgar Allan Poe reference there, right? Because it is despair, right?

LV: Yeah.

PK: Is it true that there’s a video game of this movie?

LV: It doesn’t exist yet but I know that they’re working on something.

PK: Who’s working on it?

LV: Um, not me. You know when I make a film it’s quite important that people know the original, and then what they do with it afterwards I can’t control. So I’m, no, I wouldn’t work on the game.

PK: It seems like a kind of difficult game, I would imagine. A lot of that stuff you don’t want to do at home.

LV: Yes.

PK: There are a number of films that have been coming out lately—and this probably is remote to your film-making, but there’s a film coming out that’s called 2012, there’s another one called Legion; there seems to be a number of films recently about the end of the world and the apocalypse. Do you think this film draws on that kind of zeitgeist?

LV: “Zeitgeist,” yeah. Probably. But I remember a lot of films about the end of the world early on, also. And I can only say that this film that I am going to do is going to be the real end. Nobody is going to survive. Normally there’s a couple of people that will survive in a cave somewhere. Not in my film. No no no.

PK: You did a film similar to that, Epidemic, a while ago.

LV: Oh yeah that’s right. It must be zeitgeist. But that’s zeitgeist from some time ago.

PK: Yeah. So it’s not going to be your last film? If you wipe out the entire human race, you’re can go on from there. A fresh start.

LV: Yeah, you can say that. But you have to start with these little—it’s something called stromatolite, these little bacteria form that live for three billion years. If you had been there filming with a camera, it would have taken you three billion years to get just a little action.

PK: And then you’d probably regret it, too. I think that three or four of your last films have been set in America, and you’ve never traveled to this country. What is the reason for that?

LV: First of all, because I’m afraid of travelling and the travels I’ve done have not been very successful. To me, you know, 80% of the films that I like and that I’ve seen have been American. So, to me, America, since I have not been there, is some kind of a “film-land,” you know. So I can do almost whatever I want to because I don’t know the place. I think the next one will not be in America, but of course for a film to be marketable it must be in English or American, I’m just not comfortable with setting it in a country with a different language.

PK: And it’s usually in the Northwest, too. The Pacific Northwest.

LV: Yes. That’s because somebody told me that it looks like Scandinavia.

PK: Twin Peaks was in the Northwest, was it? Wasn’t that one of your favorite movies or TV shows.

LV: Oh yeah, I believe it was. Or maybe it wasn’t.

PK: One of the prizes that the film received at Cannes was kind of ironic. It was the “anti-prize” from the Ecumenical jury. Do they give you some sort of trophy for that?

LV: No, I didn’t even know about that. But I’m proud.

PK: I thought it was a bit hypocritical because the head of the jury was somebody who worked with Marco Ferreri, who had done The Last Woman, which involved Gerard Depardieu in a scene similar to one in your movie. Why do you think people get so worked up about your film, but that one I don’t recall having so much controversy attached to it.

LV: No, but that was in another time, you know. Yeah, I don’t know.There was a lot of nudity and violence and ecstasy also in the seventies, wasn’t it?

PK: Yeah I think it was ’76 or something like that. Would you have preferred to make movies back then? There seemed to be a more open, creative, atmosphere for filmmakers all over the world, including the United States.

LV: No, I would say that the only trick I have up my sleeve is to take something from back then and show it today. So no no, if I had done it then, I would have disappeared, you know.

PK: The film that’s coming out here around Halloween, which I don’t think you have—do you have a similar holiday in Denmark?

LV: We are getting more and more Halloween.

PK: And people have asked me what the film is like, and I’ve described it, and I’m probably not the only one, as kind of like Saw 6 as directed by Carl Dreyer.

LV: Yeah, very precise.

I would always be proud if any film of mine was compared to Carl Dreyer. I believe these films, are they something called torture-porn? They are torture-porn. Well it’s nothing I see, you know, the torture-porn, but I like to mix different ingredients from different genres into a film. Because I think it’s a little, I think that the genres could be—well, hello!

[my editor enters the room where I am having this conversation and looks at the screen]

PK: That’s my editor! I can’t kick him out. He thought you were a DVD, you’re not a DVD, are you? No, no, you’re real. Sorry about that! You were talking about torture-porn and how you like to mix genres.

LV: Yeah, I don’t have a kind of moral thing about torture-porn or porn altogether. I think, I believe that anything you can imagine you could show. But of course I have children also. But in principle I think you can show anything.

Woman’s voice: Sir, we have to end here…

PK: Okay. I was surprised when I was reading material about previous interviews that you converted to Catholicism in 1995? Is that, do you still practice that?

LV: No, I didn’t convert because I was a-religious before and after some years you tend to be more and more like your mother and father, and they were atheists by belief, so I am a poor Catholic.

PK: But do you believe in redemption?

LV: Ah, that’s a long question. Yes, let’s say.

PK: Oh, what a relief! Alright, well thank you very much. Happy Halloween! Bye-bye.