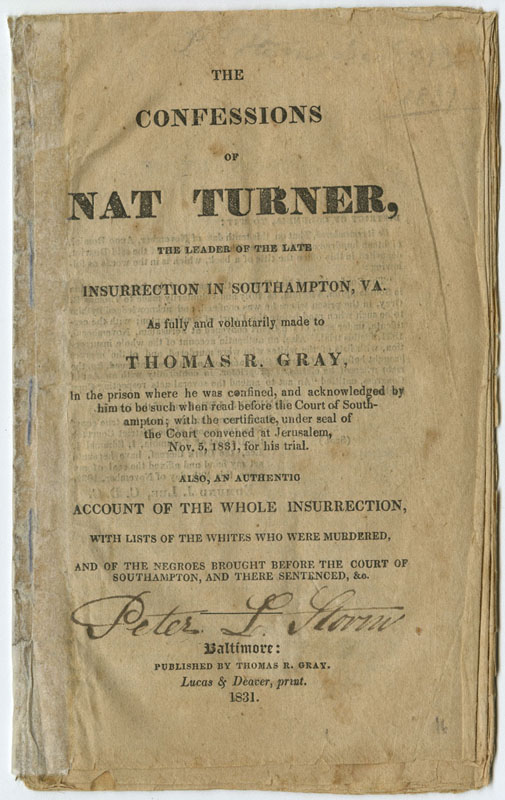

Yesterday I did a two minute sound bite on a local cable news station following the Oscar nominations. During this discussion, in addition to forgetting Robert Redford’s name, I said that I thought Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave had a good shot at winning the Best Picture Award, making it the first film by a black director to do so. And who knows, maybe McQueen would win Best Director too, another first.

Not exactly stepping out on a limb there. But then I added that I hoped 12 Years did win. Before I could explain my reasons for this, we were on the topic of snubbed performances and that’s when I blanked on Redford’s name (now that I think of it I also forgot to mention the cat, or cats, in Inside Llewyn Davis, who I thought should have gotten some recognition. Damn!)

After the broadcast, my colleague Laura Frank Clifford, who was kind enough to watch, mentioned via Facebook (and I thank her for overlooking my Redford senior moment) that my endorsement of 12 Years a Slave seemed to contradict an earlier posting on Artsfuse where I had in fact listed the film among as number one among the worst films of 2013.

Another senior moment? Perhaps not. As I noted to Laura, that “worst” film list referred not necessarily to really awful films, but to films that either failed miserably to live up to expectations or were vastly overrated (okay, an amended list also included Grown Ups 2 and A Madea Christmas, which were indeed very awful films). And my reservations about the film remain – I am definitely with Gerald Peary and Jonathan Rosenbaum and even the printable version of Armond White’s opinion on this one.

At any rate, if quality was the issue I would not think 12 Years is deserving of the Best Picture Oscar. It’s not the worst of the nominees (I’d award that prize to Gravity, which barely missed inclusion in my ten worst list) nor the best (I’d go with Her, but probably would have opted for Llewyn Davis if it made the cut).

But as all but the most ingenuous or disingenuous would acknowledge, quality has little to do with who gets an Oscar. It is about image and p.r. and politics and making money.

Image-wise, an Oscar for 12 Years could serve to counter the Academy’s well-deserved reputation as a segregated bastion of white, male, middle-aged privilege that has denied access and recognition to minorities and women. It would be a historic first, a sign of better times to come! Just like giving Kathryn Bigelow Best Picture and Best Director Oscars for The Hurt Locker in 2009. And we all know how that threw open the doors for women directors in Hollywood.

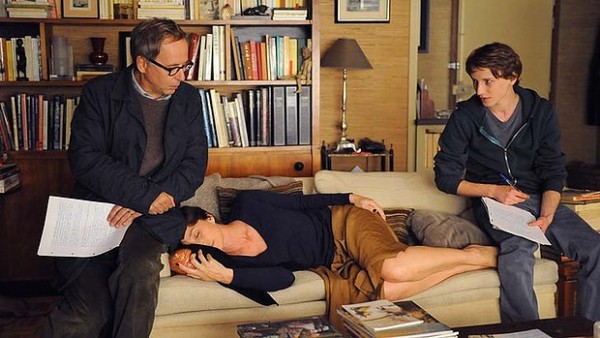

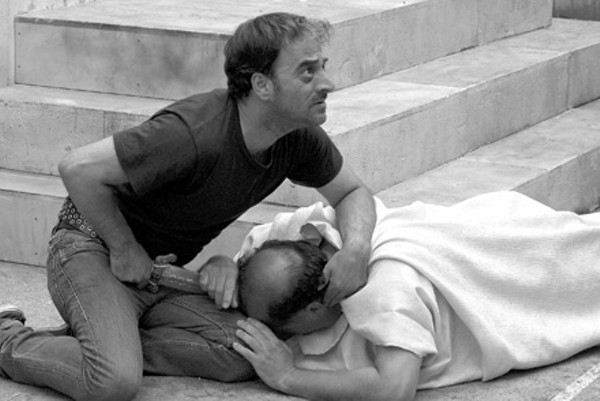

It would be great for Hollywood’s image, then, but substantively meaningless when it comes to opportunities for black or other minority filmmakers. It’s an award that would honor the Academy more than the recipient. As was the case with Bigelow, McQueen doesn’t need this bogus imprimatur to prove that he is a brilliant filmmaker. Though not a fan of 12 Years, I believe his previous two films, Hunger (2009) and Shame (2011) are evidence of a major auteur. Whether he gets an Oscar or not, he’ll be making many great films and has at least a few masterpieces in him.

So I don’t think 12 Years should win the Best Picture Oscar either because it is the best film among those nominated or because it can serve as a token gesture that will make no difference in the fundamental racial imbalance of Hollywood. I think it should win because it might get more people to watch it.

I’m not talking about the already converted, those who know that slavery was an abomination and should not be forgotten or forgiven and who realize that the malignant racism that engendered that monstrous institution still lies not so far below the surface in our society.

Nor am I talking about those unembarrassed by their recidivist racial attitudes, like the fans and defenders of Phil Robertson of Duck Dynasty who agree with his belief that African-Americans had it pretty good before the Civil Rights movement made them all uppity and angry. People like Sarah Palin, Newt Gingrich, Ted Cruz, etc… For if even by some miracle those people are prodded into watching the film, they will no doubt dismiss it as a fabrication by the left wing traitors of Hollywood and the liberal-biased lame stream media.

Instead, those who would most benefit from watching the film are those who feel satisfied that the battle for racial justice is a done deal. And maybe overdone. These are people who don’t think much about these issues but who if pressed might be on the fence about whether we’re making too much of a fuss out of voting rights, equal opportunity, social programs for the poor. You know, the kinds of things that Martin Luther King Jr. and others spent decades fighting, and sometimes dying for.

It’s not an easy movie to watch. And in some ways it’s not even a very good movie. But it is a brutally efficient history lesson. It tells the truth about a terrible thing that most people would just like to forget about. If giving an Oscar to 12 Years a Slave in any way helps preserve the progress we’ve made in the 149 years since slavery was abolished, I’ll be rooting for it.