Jonathan Glazer’s “Under the Skin,” released on Blu-ray yesterday (July 15) might be the best film in a year with many candidates. In it Scarlett Johansson (who’s proven to be adept at portrayng non-human characters such as in “Her” and “Vicky Cristina Barcelona”) plays a tarty looking woman cruising Glasgow in search of horny, heedless men.

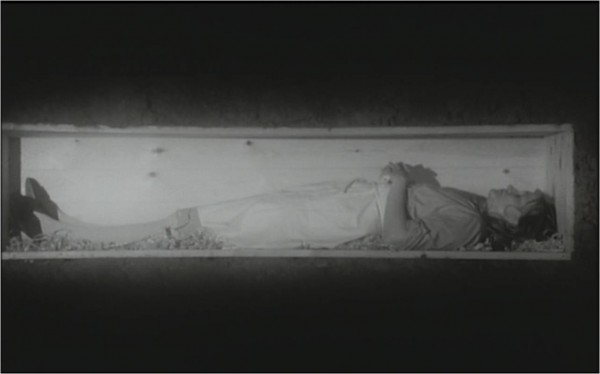

She lures them into an endless, black, mirrored room where…

At any rate she’s an alien predator and is good at her job. With uncanny music by Mica Levi, cinematography by Daniel Landin that is both otherworldy and brutally mundane, this loose adaptation of the Michel Faber novel insinuates the viewer into the point of view of a ruthless Other, and by the end blurs the distinction between the human and inhuman, achieving a cold kind of transcendence.

In a 13-year movie career, Glazer, an award-winning director of commercials and music videos, has made only two other features – “Sexy Beast” (2000) and “Birth” (2004). His pace is Kubrickian, but you might not want to make that comparison, as I did when I interviewed him for the Boston Globe when he was promoting the movie earlier this year. Here’s the transcription of that interview, minus the bits used in the Globe feature which you can find here:

Q. This film requires at least two screenings. For example, the first time I saw it I didn’t pick up the word “film” in the hallucinogenic opening sequence.

JG: I hope it would stand repeated viewings. I have never seen the film for the first time. So I would assume I’m in an impossible situation to answer that. So I’m probably the worst person in the world to ask that. What I see I know, and worse still, I know what comes next. So I’m anticipating every single cut while I’m watching it, and until I forget every cut I won’t be able to see what it is.

Q. Since it was largely, shot often in a cinema-verité style, and includes real people, is it a kind of documentary?

JG: There is a – don’t know what the term is. But it involves the interaction with the real world. And using that to tell the story. People have obviously been shooting films in the real world for decades. There’s nothing new there at all. What’s new here is the use of character. The methodology is very correlated to the story.

Q. Those are real-life people who enter the black room?

JG. Yes. I’d get them to sign the release form on the way down. Some of them are – everybody we cast because I knew we needed certain people for certain sequences. Clearly need to be aware of what they’re doing. So some of those characters are cast before the filming. But they needed to match the reality of the people who weren’t cast. It couldn’t suddenly be an acted film. It couldn’t go from that to being an acted film. I needed that kind of texture and tone, the sense of her being the only fabrication of the film. But it’s interesting that you asked the question because that’s a good indicator that it worked. That you’re not sure who’s who. Who was cast and wasn’t cast.

It’s funny talking about this stuff now because this never used to be the case that there was such an appetite to know about how a film was made before it even came out like now. I’m sure this is the digital monster we feed. But I think it’s important not to demystify things that we might spoil the way people view the film. Spoilers, yeah. And I don’t know if that spoils the way people see the film. Or whether people would have that in their head – is he real or isn’t he?

Q Is the deformed man a real person or an actor? [Towards the end of the film Johansson’s character picks up a disfigured man].

JG: He’s not an actor but he was cast before we filmed.

Q: Is he really deformed?

Yeah. He wants more of it. He’s into being into other films and other projects. He’s really very brave. He’s a unique character, Adam [Pearson]. He’s a very funny man. And very…amazing confidence. He’s not anything like the character in the film. I think he has the same condition as the Elephant Man, neurofibromatosis. Where the nerve endings keep growing.

Q.Would you say that this scene is a turning point in the audience’s empathy with Johansson’s character?

JG. It is where you begin to care for her. But empathy comes from a truthful performance. If you’re filming a saint or sinner empathy will follow the truth of their behavior. And … Which it does. We put that on her. Our understanding of things, our intention was to think of her like, a force. And when you make a scene like [one involving parents and a baby at the beach in which the alien demonstrates shockingly cold-blooded behavior ] you know what you’re doing… when you’re sitting in a room with your feet up on the table looking into the distance for month after month … when you’re writing. What you’re thinking about at that stage of the story how do you show her, that she has nothing that we have, that she feels nothing that we feel but also shows simultaneously what we are. In a scene like that I think her looking at us… we see a tragedy. But she’s not looking at what we’re looking at. It’s like she’s looking at that cactus or that napkin. We think about at what point we will lose all empathy for that character –if we kill a dog, or abandon a child…

Q. But somehow the film switches gears.

JG: It begins when she has stopped at an intersection and looks around wondering where that sound [of a baby crying] is coming from. And we saw that sound happening over there ten miles away [in the beach scene]. She’s remembering that. Then she sees the child sitting alongside her in the car and … probably because he dropped his bottle or something… and she looks at the child. That’s the first time we see her look away from her hunt, her focus. She has that residue of memory. Maybe there is curiosity. It’s the first note. Whether people will read it like that, that’s what it will feel like. That is the intention of that.

I discard all the stuff people expect in a narrative. There’s little dialogue. It’s told from her point of view. Another logic in the film is that if you understand how she feels you understand where we are in the story. There is a plot there. In the same way – this an example of what we got rid of and what we kept and how we worked things out for ourselves. We show the meat train [the final destination of part of the men who have been seduced]. But we don’t know what that’s for. The stuff could be woven into thread for fishing line to catch space monsters. A wallet. Anything. None of those answers are interesting. As far as we’re concerned the story we were telling and how we wanted to tell it that’s good indicator of why we stopped and why.

Q: In “Birth” Alexandre Desplat composed the score. He’s been nominated six times for an Oscar. Here you are collaborating with Mica Levi. It’s her first movie. Why this choice?

JG: This needed a new voice. Mica is that. It feels from somewhere else. It’s the blood of the film.

For instance, in the beginning there is music with the cycle of her predecessor, and at the end the music starts again. It’s a slightly different rendition but it’s essentially the same thing. The music you hear at the beginning with that alien kind of appetite. So it’s back to business again. So the music is doing the business of pictures. Or words. It’s less obvious and less easy to pick up but it is there. This is the language we wanted to make the film in. not for me it’s not too subtle. And you’ve got to do what you think is best.

I think if you can sustain… “Vertigo” is an important film for me in that sense. I remember seeing “Vertigo” and just being absolutely struck that 20 minutes had passed and absolutely not a word was spoken. And I was utterly gripped. The absence of words – just what your shown and what you hear is utterly gripping. To not feel like you need to have things explained to you. Or have words defuse something as they can. They can charge something when they have to be used and should be used. But just the blah blah blah of most scripts.

Q: After nine years of working on this movie and now having finished it, how do you feel?

JG: I’m bereft

Q: You’re being ironic.

JG: It’s somewhat true.

I’m looking for my next thing. It’s not like, get me another script! The next thing that insists itself on me. “Birth”

was one that spun out from me. Then I took it to Jean Claude [Carrière] and – I had a paragraph at the time and I told him the idea and he really liked it. Then we did a long period of work.

I do have this thing – it’s connected with a book… But I don’t know what I’m doing next. Something will come up and say, “what do you think?”

Q: Nine years between movies? That’s a Kubrickian pace.

JG: I’m an infant compared to Stanley Kubrick. There is… I admire the mastery of the man the way that everyone does. Completely. I admire his fearlessness. That’s the key. That’s the key to art.

Q: Would you say that there’s a fairy tale quality to the ending of “Under the Skin,” a kind of Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf thing?

JG: I suppose there are elements of that. I think it’s a happy ending, actually.

Q. I’d hate to see what you think is an unhappy ending. How is it a happy ending?

JG: Well. For me she’s becoming part of the world in a way she couldn’t be otherwise. She’s aching towards that, isn’t she? She achieves it in a horrible way.

Q: Isn’t it odd that in Scarlett Johansson’s last two movies she plays a non-human? She has a knack for it.

JG: [looks skeptical]

PK: It’s a compliment.

JG: I’ll pass it on. She’s great.

“Christmas comes but once a year” is beginning to sound more like a promise from the major Hollywood studios than an expression of seasonal joy. There were some good films worth discussing; some bad films worth excoriating. But mostly we were served helpings a plain, squishy vanilla, movies so devoid of, well, almost anything, that they evoke as much a discussion as “Didja like it?” “Eh.”

“Christmas comes but once a year” is beginning to sound more like a promise from the major Hollywood studios than an expression of seasonal joy. There were some good films worth discussing; some bad films worth excoriating. But mostly we were served helpings a plain, squishy vanilla, movies so devoid of, well, almost anything, that they evoke as much a discussion as “Didja like it?” “Eh.”